I’ve been reading Mrs. Dalloway at the rate of about fifteen pages a day. It’s all I can manage. The book reads like wonderful dark chocolate. It cannot be eaten quickly, but savored, and just a small bit satisfies. Two nights ago I finally reached the chapters of Mrs. Dalloway’s party. I love how Virginia Woolf used her words and sentence structures to convey the motion and energy of the party. As the reader, you feel that you are in the middle of its whirl. Most of the characters, whom you have come to intimately know, are present. And you are a guest there like the others.

Yesterday afternoon as I was cleaning my desk, I came across some pages I had printed from Etiquette: What To Do, and How To Do It, by Lady Constance Eleanora C. Howard, and published in 1885. I smiled as I read the pages, thinking of Mrs. Dalloway’s party. Although Lady Constance Howard goes into depth about the etiquette at balls, dinners, luncheons, etc., I opted to excerpt the pages on giving teas because I haven’t posted anything about teas before. I must admit, reading this description was rather stressful. I could never give an “At Home” for I would inadvertently insult all my acquaintances. Good heavens, I might use the wrong invitation format or introduce the wrong people or have my imaginary servants stationed in the wrong rooms. Teas are an etiquette minefield and not for the faint-hearted, casual hostess.

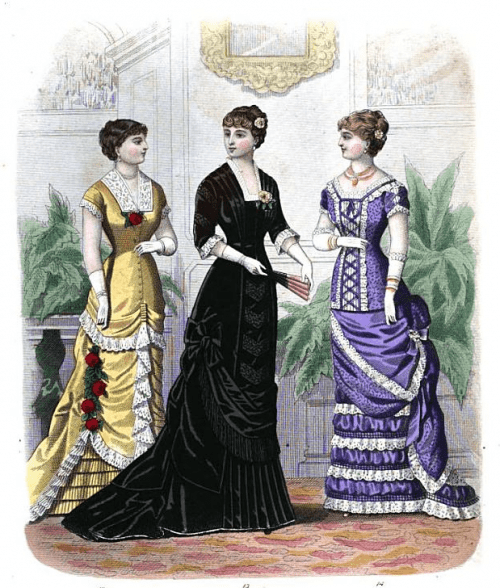

The images are taken from The London and Paris Ladies’ Magazine of Fashion, from 1881

‘Five-o’clock Tea’ makes an agreeable break between luncheon and dinner, and is welcomed by all, whether ladies who have been riding or walking, or just arrived from a journey, or by keen sportsmen after a day’s

shooting or hunting.

In many country houses it is the custom to have ‘School-room Tea,’ to which all the guests are bidden ; they come, or not, as it pleases them. In some houses, the hostess only receives a few intimate friends in her boudoir, but most generally tea is served in the drawing-room, or library, or hall, when the latter is arranged as a sitting-room—often the case both in London and the country.

The usual way is to have a low table covered with a pretty cloth embroidered with, say ‘poppies, wheat and cornflowers.’

On this should be placed the teapot, cream, and milk jugs, sugar and slop basins, cups and saucers, each having a teaspoon, and plates.

Another table has plates of brown and white bread, little cakes, scones or muffins, in the winter, and jam, honey or marmalade.

When guests are expected from a journey it is usual to add sandwiches of game or potted meat, and to have a tray with sherry, brandy, and seltzer on another table for those who prefer it to tea.

The hostess would pour out the tea, saying to each guest,—’ Do you take sugar?’ and ‘ Will you take cream or only milk?’

Then she hands the cups to the gentlemen, who, in their turn, hand them to the ladies who are sitting about the room in groups.

Conversation would be general at ‘ five-o’clock teas,’ as the number of guests does not generally admit of ‘tête-à-têtes.’

The gentlemen would hand the cakes, etc., to the ladies in the same way as the tea, saying,— ‘May I give you some cake or muffin?’ at the same time seeing that each lady had a plate. Plates should always be used at five-o’clock tea, just as much as they are at any other meal. There can be no possible reason why they should not be—people cannot put their cake or scone in their saucers, nor on the table, as that would be very vulgar—therefore plates are an imperative necessity; also slop basins, as no one likes the dregs of a previous cup of tea left in their cup if they wish to take a second.

Knives are only used for cutting a cake, not by each person, unless toast is provided, with butter, jam, honey, or marmalade, when they are necessary to spread these condiments.

Serviettes are never used at five-o’clock tea. Hot water to replenish the teapot should be sent up in an urn, a silver or china kettle, or a jug with a silver or plated top; it is sometimes put in a silver jug, but it is not a good plan as the water so soon gets cold in them. The teaspoons should if possible be silver, and sometimes teapot, sugar-basin, cream and milk jug, are in silver, as also the sugar-tongs; where this is too expensive, all china takes its place, in which the service is either all one pattern or else ‘harlequin.’

Scones, muffins, buttered toast should be served in dishes with covers to keep them hot.

Salt should always be sent up, as many people eat it with bread and butter, etc.—a small silver muffineer is best for it.

China or coloured Venetian glass dishes are best for butter, jam, etc.

Some people add mustard, cress and radishes, but this is not generally done.

The footman would place the tables in their proper places, cover them with the tea-cloths, and then carry in a tray with the various things needful.

The butler would place them on the tables, and then they would both leave the room, as it is not usual for servants to wait upon the guests at these meals; they wait upon each other, which is far less formal and much more agreeable.

Where no men-servants are kept, the parlour-maid would do exactly the same.

‘Five-o’clock tea’ in London is a very different thing. Ladies like it extremely; gentlemen, as a rule, detest it most cordially.

Generally say fifty ladies and five gentlemen is about the average at these assemblages, so that the ladies are all powerful, being in such an overwhelming majority.

The reason is this, ladies like them because at ‘five-o’clock teas ‘ they form new acquaintances, meet their favourite friends, make numerous plans for further meetings, and future interchange of civilities and entertainments; and, although as a rule few gentlemen put in an appearance at ‘five o’clock tea’ in London, considering this form of gathering too insipid; if they do honour it by their presence at rare intervals it is either because they want to meet a particular lady, or as a compliment to a popular hostess, one at whose house it is the correct thing to be seen, and where absence would proclaim that they were not on her list of friends and acquaintances. Yet, ladies are always ready, even in the middle of the rush of the London season, to look in at ‘five o’clock tea’ for twenty minutes or half-an-hour, if they cannot remain longer, in the course of their afternoon drive.

The refreshment of a cup of tea, whether in summer or winter, is at all times an agreeable and welcome one.

Invitations to ‘five-o’clock teas’ are either given verbally, by the intending hostess saying to any friend or acquaintance, lady or gentleman, whom she meets and wishes to invite,—

‘Will you come to me to-morrow, Mrs Green, at five o’clock, and have a cup of tea? You will find a few mutual friends.’

Or else invitations are issued on an ordinary visiting card, not on the cards used for ‘at homes’ or ‘ balls.’ The following is the correct form to use:—

the word ‘ music’ would be added if any, whether amateur or professional were to be provided, and the letters,’ R. S. V. P.,’ signifying ‘ Reponse s’il vous plait,’ or ‘an answer is requested,’ where one is wished for.

‘R. S. V. P.’ would be written on the right-hand corner of the invitation card, when such is the case, and where these letters are put, an immediate answer should be forwarded; at the same time it is unusual to require an answer, as it is generally of no consequence how many people avail themselves of such an invitation, or what numbers are conspicuous by their absence.

If, however, any of those invited are aware, when they receive the card, that it is quite certain they cannot accept the invitation, it would only be a mark of courtesy to send excuses at once.

Strict etiquette does not require this civility, but good-breeding and politeness, such as those ought to possess who go into society, would make it a matter of course.

‘Five-o’clock teas ‘ may be classed under three distinct heads, as they are varied in the number of guests invited to them.

Both invitations and replies can be sent by post, or if a lady is out driving it is customary that if she needs an object for her afternoon drive, she should make a list of her proposed guests, and leave at any rate some of the cards herself.

Cards should be left by those who have been present within a week of the tea.

At ceremonious teas, it is usual to give a fortnight’s notice; for smaller ones the invitation should be sent out about a week before; for very small teas, a couple of days’ notice is sufficient.

Some ladies, for small teas, are at home a given day each week; for instance, all the Tuesdays in May, or all the Fridays in July.

This is a very good plan, as it admits of people choosing the week most convenient to them, so that if one Tuesday does not suit, the next or the one following may do so.

A ceremonious tea consists of from fifty to a hundred and fifty or two hundred guests; when this number have been invited, it is customary to provide some amusement for them, such as vocal or instrumental music, with amateur and professional performers; the music should be as good as possible, though not important enough to be actually a ‘ concert.’

The semi-ceremonious tea numbers forty to a hundred people, then recitations, good amateur talent, vocal or instrumental, is enough to amuse people and take off any formality and shyness. I think the most agreeable teas consist of ten to twenty-five people, who all are more or less acquainted, then general conversation or tête-à-tête chats take the place of music, or any other form of instructing and amusing people, intimate friends, not merely acquaintances, and comparative strangers, forming the majority of these ‘sans gêne’ gatherings.

It would not be etiquette to put ‘ five-o’clock tea’ on the card of invitation; if the hostess invited a guest personally, she would use the words ‘afternoon tea ;’ she would not say,’ Will you come to a kettledrum?’ that expression is obsolete; the correct term for ‘five-o’clock tea’ is ‘At Home,’ except when spoken of in conversation or verbally, then they would be mentioned, and allusion made to them as ‘five o’clock tea,’ just as a reception of a few friends after dinner is always called an ‘At Home’; never should ‘evening party’ be printed or written on the card of invitation; society recognises no such sentence with regard to the invitation to such an entertainment, although in talking to a friend it would be correct to say,—’ I am going to a party at the Duke of B.’s to-night,’ never, ‘I am going to an At Home at H— House.’

Terms correct in conversation would be incorrect, pedantic, and show ignorance in the matter of a written or printed invitation.

The name of the host does not appear on the invitations to ‘At Homes’ or ‘ five-o’clock teas.’ The name of the hostess only, not the united names of the host and hostess, appears upon the cards.

In sending an invitation, the hostess would include the husband of her guest in the invitation as follows :—’ Mr and Mrs de L’Isle ‘ would be written at the right-hand corner of the visitingcard; where it is a father and daughter,—’ Colonel and Miss or the Misses F.’

The sons in a family would receive separate cards of invitation; thus, ‘Lord G.,’ or ‘The Hon. B. Turner;’ and where there is a whole family to be invited, it would be ‘The Duke and Duchess of C, and Lady D. M.,’ or the ‘Ladies M.’

If only a mother and daughter, or daughters, ‘Lady C. and Miss C.,’ or the ‘ Misses C.,’ if the wife of a baronet or knight; if a Marchioness, it would be ‘The Marchioness of W. and Lady C. H.,’ or the ‘Ladies H.;’ a Countess, the correct term is, ‘The Countess of G. and Lady H. R.,’ or ‘Ladies R. ;’ a Viscountess, ‘The Viscountess L. and Honourable Mary B.,’ or ‘Honourable Misses B.;’ the same for a Baroness when she is a Peeress in her own right, such as Baroness Burdett Coutts, Baroness Berners, Baroness Bolsover, etc. ; when such is not the case, it would be ‘Lady F. and Honourable E. V.,’ or ‘Honourable Misses D.,’ unless there were only one daughter, when it would be ‘Honourable Miss D.’

Titles are recognised on invitation cards, but complimentary denominations, such as K.C.B., K.T., etc., are only written on the envelopes in which the cards are sent, not on the cards themselves.

Cloak-rooms are only necessary at very large formal teas, when the dress of the ladies is more magnificent, and probably a long velvet coat in winter, or a light dolman in summer, is thrown over the wearer’s dress in the carriage, which she is glad to lay aside while having her tea. At small teas it is not necessary, as rooms are less hot and more empty, and the dresses of a more simple description.

The hats, sticks or umbrellas, and overcoats of the gentlemen, at small or large teas, are always left in the hall, when a servant takes charge of them until they leave.

When those who have been invited arrive, they walk straight into the house, without asking is ‘Lady B. at home?’ as they know that such is the case.

Except at large teas, when the names of those present appear in the Morning Post next day, it is not correct for a lady’s servant to give her name to the servant who answers the door, and the house door should be left open until all the guests have arrived, or each person would have to ring the bell. The only time when it is allowable to station a servant on the steps, who rings as each guest arrives, and says, ‘Coming in,’ is in winter, when an open door for so long a time would make the house cold, and be disagreeable to those already assembled.

Red cloth is never put down at any party, whether ball, concert, theatricals, at home, five-o’clock tea, except when Royalty is present.

An awning should always be provided, whether it is an afternoon gathering or an evening party, as a protection against bad weather.

When visitors are ready to leave, they give their names to the servant, who stands by the door in readiness, he passes it to the lady’s footman (if she has one), who departs in search of her carriage, and announces it when it comes up; or when there is no footman, the linkman shouts out the name, and calls it out on the arrival of the carriage.

At ‘teas’ and ‘at homes’ the hostess does not ring for the door to be opened for the guest who is leaving, or for the carriage to be called, but the guests descend into the hall, where the servants of the house call the carriages as they are requested to do so by those present.

Owing to the short time that ladies, as a rule, remain at ‘five-o’clock teas,’ carriages should always be kept ‘waiting ;’ and those invited to the tea remain in the dining-room, taking refreshment, or stand in the hall alone, or chatting to their friends and acquaintances until they hear their carriage announced.

If a gentleman were present when a lady was waiting for her carriage with whom she was acquainted, he would politely offer her his arm and conduct her down the steps to her carriage; he would assist her to get in, and if he knew her well he would shake hands with her; if he was merely an acquaintance of recent date, he would make her a low bow only, as the carriage drives off, not offering to shake hands unless the lady showed a wish to do so.

Refreshments at ceremonious teas are always served in the dining-room, and a long buffet is placed at one end of the room, behind which stands the lady’s maid, etc., who pour out the cups of tea and coffee, and hand them across the table to those who ask for them, replenishing the cups when necessary.

The lady’s maid is always present on these occasions, as well as the Butler and footman; the Butler sees that the gentlemen have claret cup, wine, etc

The tea and coffee should be in silver urns, and the buffet prettily decorated with the flowers that are in season, fancy biscuits, brown and white bread and butter cut very thin, plum, seed and pound cakes, and macaroons and sponge cakes are placed upon the buffet, while sherry, champagne, and claret cup, lemonade, ices, fruit, potted game, sandwiches, and in the summer, china bowls heaped with strawberries, and dishes of whipt cream, and in the winter ‘maroons glacés’ are all placed upon the centre table.

Plates are always provided—ice plates for the ices, ‘which should be both cream and water with waifers,’ and small plates for fruit, with a place for the pounded sugar.

Tea in the dining-room, whether the party is large or small, is the most convenient; it saves carrying all the necessary paraphernalia upstairs. If the number of guests is very small, it might look unsociable to assemble in the dining-room, as it would leave the hostess alone, she not being able to quit her post until the majority of the guests had arrived.

Therefore, at very small and intimate teas, the refreshments are served in a small boudoir, or ante-room, or where there are two drawing-rooms in the inner one of the two.

The refreshments are of the same character as at the ceremonious parties, but on a much more pretentious scale; teapots are used instead of urns; fruit and ices are not provided. The hostess pours out the tea and coffee, assisted by her daughter or daughters if she has any, and the gentlemen present hand the cups and the cakes, etc., to the rest of the ladies, and then help themselves to wine, or cup, as they may wish. At teas served in the drawing-room, the lady’s maid and butler are not present. At formal teas, the servants or the maid on the arrival of each guest would inquire if they would take tea or coffee, and if they wish for either, would show them into the dining-room, where the guests would partake of refreshments, and then the servants would usher them into the drawing-room.

It is more courteous to proceed upstairs immediately on arrival, and to take tea or coffee after you have made your bow to your hostess.

The servant precedes the guests up the stairs.

At large teas, the hostess receives her friends at the drawing-room door, or on the landing; she shakes hands with each guest on arrival, whether she is previously acquainted with them or not, or in the case where a friend has asked her for an invitation for some lady or gentleman who is anxious to be present at her party.

She stands just in the doorway, the door remaining open all the time, the contrary being the case at small teas, when the hostess receives her friends within the room, advancing a few steps to meet each new arrival.

Unless a hostess is lame or very old, etiquette requires that she should move about the room among her guests, and see that they have someone to talk to, that they have tea, etc., talking with each person for a few minutes.

Her daughter or daughters would help her in like manner; no hostess would remain seated in one particular seat all the time, unless she was too lame or infirm to move about.

It is etiquette for ladies to move about the rooms at afternoon teas, and speak to their particular friends and acquaintances; there is no necessity for them to remain transfixed to one spot, unless they wish to do so, or the conversation they are engaged in is very absorbing.

Those ladies who are already acquainted would take this opportunity of speaking and making some polite or necessary remarks, but general introductions at ‘five-o’clock teas ‘ are not usual, only occasional ones, where the hostess thinks that two people would value such an introduction when they are likely to appreciate such an acquaintance, where the acquaintance has been desired by the lady, or by both, or some reason of similar importance.

In a formal, or semi-formal manner, the hostess, if she judged it wise to do so, would introduce some of the ladies present to each other, but she would never do so unless she was quite certain beforehand that they would have no objection to the introduction.

Then she would say, with a view to drawing the ladies into conversation, ‘Lady Z., I don’t think you know Lady L.,’ when the ladies would acknowledge the introduction by a bow; or,’ Mrs V. and I were talking about the first night of Romeo and Juliet, are you going to it, Mrs D.?’ In the same way, the hostess, if she saw Mrs D. knew no one of the gentlemen present, she would say, ‘May I introduce Lord N. to you, Mrs D. ?’ at the same moment bringing him with her to the lady she addressed, who would smile and bow. Lord N. would then say, ‘Will you let me get you some tea?’ he would not say ‘May I get you some refreshments?’ that would be very vulgar indeed, and if Mrs D. consented, Lord N. would offer her his right arm, and would conduct her to where the tea was served.

The hostess would be very particular that the ladies of highest position present were escorted to tea in the intervals between music, singing, conjuring, recitations, or whatever amusements she had provided for their benefit and amusement, and would introduce gentlemen to them, if there was no one by at the moment that they were acquainted with, that they might then show them this politeness of society.

The host, if there is one, would take the ladies of highest rank to tea.

All the gentlemen are expected to be constantly escorting ladies to tea, so they do not remain in the dining-room many minutes, therefore seats as a rule are not provided, as they remain there so very short a time; gentlemen conduct the ladies back to the drawing-room when they have finished their tea, as it would be a great incivility on the part of a gentleman were he to leave the lady alone in the dining-room, or let her find her way upstairs without his escort.

Having found her a seat, he would make her a polite bow, and proceed to escort someone else to tea. Should, however, the lady not wish to return to the drawing-room, the gentleman would remain talking to her until her carriage was announced, when he would escort her to it.

Several ladies would, at the suggestion of the hostess, go to tea together, when the gentlemen were in the minority; their hostess would say a few words of civil excuse for their absence.

Punctuality is not necessary at ‘five-o’clock teas,’ the hour named allowing the guests to come when they like, and leave when it pleases them—some stay a long time, others only a few moments; it entirely depends upon their inclinations and motives for being there. Few, if any, remain the whole three or three hours and a-half specified on the invitation card. Sometimes the latest arrival stay the shortest time; at others, the earliest leave after a few minutes, from five to six being the most popular hours for arriving. People going on to other ‘teas’ in the same afternoon, as often happens, would either come earlier or later than these hours to allow of fulfilling both engagements.

Gentlemen generally stand about the room talking to the ladies at these parties when taking tea or wine, etc.

If a gentleman saw a lady with an empty cup in her hand, he would politely put it down for her, otherwise the lady would place it on any table near to her.

Cream and sugar are handed to each guest by the gentlemen, as a matter of course. It would not be etiquette for the hostess to inquire if her guests take them; ladies would ask for a second cup of tea if they were thirsty, but it would be against etiquette, and look peculiar, if they did not take tea or coffee, and asked for chocolate, milk and soda, cocoa, hot milk, cider, or some beverage not usually served at tea.

If they did not like the refreshment provided, without entering into any explanations they would simply say, ‘No tea ; thank you very much.’

A lady intending to eat ices, cake, bread and butter, fruit or sandwiches, would take off her gloves, but not if she simply had tea or coffee without eating anything.

Etiquette does not make it imperative that guests should take leave of their host and hostess at ‘five-o’clock teas,’ unless it were late, and few people were left, in which case these guests would, as politeness required, make their adieus to their hostess, and if it were their first visit to the house, or the hostess were a recent acquaintance, or happened to be talking to a guest on the landing, standing in the doorway, or coming back to the drawing-room from tea, then etiquette requires that the guest who was leaving should take his leave of her, with a few civil words of thanks.

Except on these occasions it is not usual to do so.

Conversation, when there is ‘music or singing’ at afternoon teas, should be indulged in in a low tone, so as not to disturb or annoy those who are doing their best to amuse the guests, at least guests should try and look as if they were listening to the performance, even if they are not ardent votaries of music.

No gratuities at this or any other entertainment to be given to the servants.

Goodness gracious, it sounds exhausting.

There are not enough hours in the day for that kind of snobbish craziness.

And no tipping the servants no matter how entertaining they are. Also, I am curious as to what occasions would NOT require a civil word of thanks. Probably if the servants were too entertaining, I imagine.

My favorite part is when she writes that men don’t often come to teas in London and then lists all the things a man must do should he foolishly wander into one. He wouldn’t even get a seat because he is so busy escorting and fetching tea.

NO SERVIETTES!!!!!!

Oh, sound terrible. I totally understand men who don’t often go to tea. 🙂

Don’t you mind if I translate this for my blog in Russian? Of course, with all the links and references. I’ve done it before and asked already for the other articles, if you remember

Szvetlana

@Smily – you are so welcome to translate. It’s all in public domain anyway…well, US public domain.