Is that an exciting blog post title or what? Total clickbait 🙂 I’m at home today, sick on the sofa. Perhaps I need a bit of bark or snakeroot from Jonathan Webb’s medicine chest.

Jonathan Webb, a chemist and apothecary in Salem, Massachusetts, sold family medicine chests to his customers in the early 1800s. A medicine chest was typically a wooden cabinet specifically designed to house medicine bottles and containers that were filled and labeled and/or numbered by the chemist. The preface of Mr. Webb’s 1818 volume, Particular Directions for a Family Medicine Chest is quite self-explanatory as to the purpose of his medicine chest.

Families would use the medicines in this chest and what grew in their gardens and surrounding lands to make popular remedies for their ailments. There are numerous old books containing recipes for these remedies that were composed of ingredients that were common to people then but sound rather exotic to the modern reader… or maybe just to me. What interests me about this little volume is that it’s essentially directions about how to use the medicines in Mr. Webb’s chest. The information is a little more contained that what I’ve found in other books.

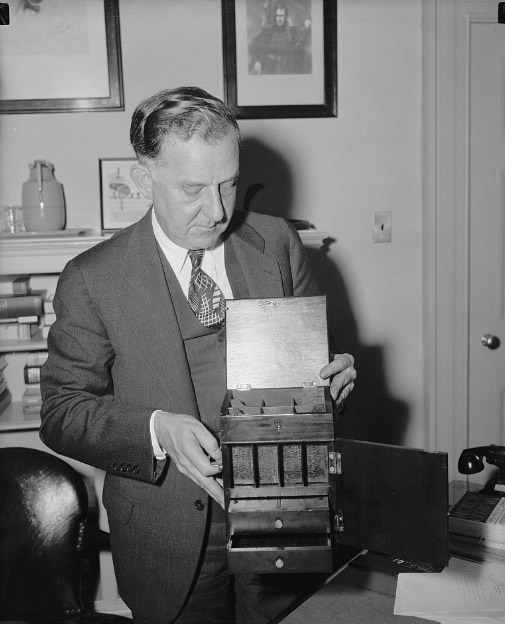

Sadly, I don’t have an image of Mr. Webb’s actual medicine chest, but I found this image in the Library of Congress. This is a medicine chest that was stolen from the White House during the War of 1812 by a sailor but later returned to the White House by the sailor’s descendants during Franklin Roosevelt’s administration.

Harris & Ewing, photographer. White House Secretary and medicine cabinet taken from White House. District of Columbia United States Washington D.C.. Washington D.C, 1939. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2016878157/.

Below is an image of a fancier medicine chest from London.

Mahogany medicine chest, England, 1801-1900. Credit: Science Museum, London. CC BY

Let’s focus on Mr. Webb’s humble chest and its contents. The box has over 50 items, but I’m going to highlight a few here.

No. 3. TINCTURE OF GUAIACUM. Good for weakness, or pain, faintness at the stomach, and for sudden cramp-like and rheumatic pains. Dose, 25 drops, once or twice a day, on sugar.

No. 5. OPODELDOC. This is a very good application for strains, bruises, &c. A little of it should be poured on a warm hand, and rubbed on the part affected; when rubbed in dry, more must be used, and the rubbing continued for some time, and the part immediately after should be covered with warm flannel.

No. 6. LAUDANUM— BE careful ! ! Good to ease pain, and procure sleep; to check the excessive operation of pukes or purges. It is given in doses from 15 to 30 drops, in tea, wine, or water. The above dose is for an adult; more may be given if the case is an extreme one. It should never be given in large doses, unless by direction of the physician. In all cases, caution is necessary.

No. 7. SPIRITS OF LAVENDER. This may be given oil sugar, or in a little wine. Dose, from 30 to 80 drops, in cases of languor, lowness of spirits, and faintness.

No. 10. BALSAM DROPS. Good in a bad cold, or in a high burning fever. Shake the phial, and give 20 or 30 drops in a little herb tea, and if necessary, repeat it two or three times a day. Keep the person warm in bed, and they will produce a free and gentle sweat.

No. 11. ELIXIR VITRIOL. Dose, from 15 to 25 drops, in a glass of water. It is good for weakness at the stomach, checks night sweats, attendant on hectic fevers, and makes an excellent gargle for inflammatory sore throats. It may be given to advantage with a decoction of any kind of Bark. It will often answer as a tonic medicine where bark fails.

No. 19. RHUBARB POWDERS. This is a gentle purge, operating without violence. In diarrhea, or in any bad purging, where gentle physic is necessary, one of these powders, (No. 19) may be given in molasses or syrup in the morning, and worked off with water gruel.

No. 23. SUGAR OF LEAD. Sugar of Lead, dissolved in equal parts of vinegar and water, makes a good wash for inflammatory swellings, caused by bruises and sprains and broken bones — one moderate spoonfull of the powder (or one of these powders) to a pint of liquid. Apply a rag dipped in it to the part, and repeat it often enough to keep it moist. When the skin is broken, omit the vinegar.

No. 25. HEALING SALVE.— (“Turner’s Cerate,) This salve, spread on a linen rag, is proper to be applied to sores, burns, scalds, or any slight disorder of the skin. It is also proper to skin over wounds, after they have been filled with flesh by No. 24, and to dress blisters.

No. 26. POWDER FOR PROUD FLESH. (Red Precipitate.) A most excellent remedy for spongy or proud flesh. Sprinkle on enough to cover the proud flesh, then lay on a piece of dry lint just large enough to cover the sore, and a pledget of Basilicon over the whole.

No. 27. DIACHYLON PLASTER. This plaster answers very well for slight wounds or sores, and to be spread on a rag, to be applied over other dressings, to keep them on the wounds.

No. 29. BARK, (Yellow.) Bark is an excellent tonic medicine, in convalescence from Typhus fevers; also in intermittent fevers and chronic rheumatism. It is much more effectual in the form of powder, where the stomach will hear it. Dose, one teaspoonfull every two or three hours, in a little wine or pure water. In extreme cases, it has been taken to the extent of one or two ounces in twenty-four hours. In cases of extreme debility, where putrid symptoms are threatened, it maybe taken to any extent the stomach will bear. When it is used in the form of decoction, pour one quart of boiling water upon an ounce of the bark, and boil away to a pint. Dose, from’ one to three table spoonfulls, every three or four hours.

No. 31. FLOWERS OF SULPHUR. Dose, one drachm in molasses; it is a good opening medicine in piles, and eruptions of the skin. In chronic Rheumatism and Gouty complaints, a teaspoonfull of this medicine, with half the quantity of Ginger powder, in a glass of milk every morning, is an excellent remedy. Mixed with hog’s fat, it makes a very good Ointment for Itch,

No. 33. BLISTERING SALVE. To be spread on soft leather, and applied to any part of the body, first rubbing the part with warm vinegar till it looks red; let the plaster remain on about twelve hours, or longer if not well drawn. After the plaster is removed, slit the raised skin, and dry up the water with a linen rag, and dress it with salve, (No. 25) twice a day. Blisters are proper in nervous fevers. When the patient is delirious, apply one to the back of the neck. They are likewise proper in convulsions and inflammation of the eyes. A Blister applied to the back of the neck, will sometimes remove a violent headache.

No. 36. SNAKEROOT. Virginia Snakeroot makes an excellent stimulant infusion, and determines to the skin. It is given in low fevers, either by itself, or decocted with Bark. One ounce will make one quart of tea. Dose, half a gill — when it is steeped with bark, add a quarter of an ounce of the root to an ounce of Bark.

No. 37. CALOMEL. (Mercury.) This is a very useful and efficacious medicine, but requires caution and judgment in its administration; it is a preparation of Mercury; and strict attention to the directions should be adhered to, or mischief may be produced by it. After bleeding, blistering, &c. one or two grains of this medicine may be given in molasses every six or eight hours, till the disease abates, unless the looseness or weakness of the patient, (both of which it increases) forbids its longer use. It is also very good in bad pleurisies. Calomel has been used for worms by a celebrated empiric, in doses of five grains each, and in some instances it has proved efficacious.

No. 41 ARROW ROOT. This is a very delicate and nutritious article, and may be taken in every complaint where nourishment is wanted. First wet a tablespoonful of the powder with a little cold water, that it may be reduced to a paste; then pour on half a pint of boiling water, stirring it at the same time, and it is done. It may be given in milk, coffee, or chocolate.

No. 43. SQUILL PILLS. From two to three of these Pills may be considered a Dose — taken at bed time, or twice a day. This is a powerful medicine in promoting expectoration, and increasing the secretion of urine; hence it is a valuable medicine in chronic Coughs and Asthmatic affections, attended with viscid phlegm, and in dropsical complaints.

No. 44. ASSAFOETIDA PILLS. This is a most valuable remedy. Its action is quick and penetrating, and it affords great and speedy relief in spasmodic, flatulent, hysteric, and hypochondriacal complaints, especially when they arise from obstructions in the bowels, Assafoetida promotes digestion, and enlivens the animal spirits, &c. From one to three of these pills may be given for a dose.

Aside from bottles of substances, there are other useful items in this chest. Okay, I admit, I added these screenshots purely because of the gorgeous period handwriting in the margins.